Were there no mothers of the Revolution?

ISSUE NO. 46 // FIGHT LIKE A MOTHER

Becca’s back!

Rebecca Grawl is back as my esteemed special guest. (Woo-hoo!) Last time she was here, we talked about the other Washington Monument — Alice Roosevelt. She also uncorked a flurry of questions and and semi-related tangents, causing me to wonder what if Alice was a boy.

Today, she’s sharing stories of the women who fought and supported the cause for independence.

Let’s jump in…

Presidential Doodler

PS Hey, guess what? In 2026, I’m partnering with Ashland Public Library for a yearlong virtual presidential series! I hope you can join us.

Women of the American Revolution

As a DC tour guide, it’s easy to showcase Revolutionary history. We have the Washington Monument and Mount Vernon to tell the story of our Commander in Chief, statues to Lafayette, Rochambeau, von Steuben, Kosciuszko, Pulaski, and other key Revolutionary figures. You can waltz into the National Archives most any day of the week (government shutdown not withstanding) to see the document that put voice to the cause.

What you won’t find (easily, at least) are the stories of the women who fought and supported the cause for independence. To quote an 1890 Washington Post editorial from Mary Smith Lockwood, “were there no mothers of the Revolution?” Of course there were. Women were right there alongside our well-known patriots and in many cases, forging a revolutionary path of their own.

In honor of America’s impending 250th birthday, here are 8 women you should know (one for each year of the American Revolution!)

Elizabeth Burgin

In 1777, Elizabeth Burgin dedicated herself to helping American prisoners of war secretly escape British custody off of prison ships. It is estimated that she aided more than 200 prisoners of war, working with George Washington’s Culper Spy Ring.

Her exploits were well-known enough that the British offered a 200 pound reward for her capture. She fled to New Jersey. When General George Washington learned of her plight, he wrote to Congress, attesting to her service and her “measures for facilitating their escape.”

In response, the War Board of Philadelphia offered her lodging and food rations. Not wanting to be a burden on the government, she wrote to Congress in 1781, suggesting she cut linen for military shirts; Congress instead paid her a pension for her wartime services.

Mercy Otis Warren

Mercy used her intellect and wordsmithing to bolster the cause of the Revolution. She and her husband James often hosted revolutionaries, including the Sons of Liberty, at their home in Plymouth, Massachusetts.

Warren was a voracious political activist and writer, corresponding and encouraging the revolutionary movement among luminaries such as John and Abigail Adams, John Hancock, Patrick Henry, George Washington, and many more.

She once wrote “every domestic enjoyment depends on the unimpaired possession of civil and religious liberty.” Warren used the power of her pen to write plays and poems about the Patriot cause as well as compiling a three volume history on the American Revolution.

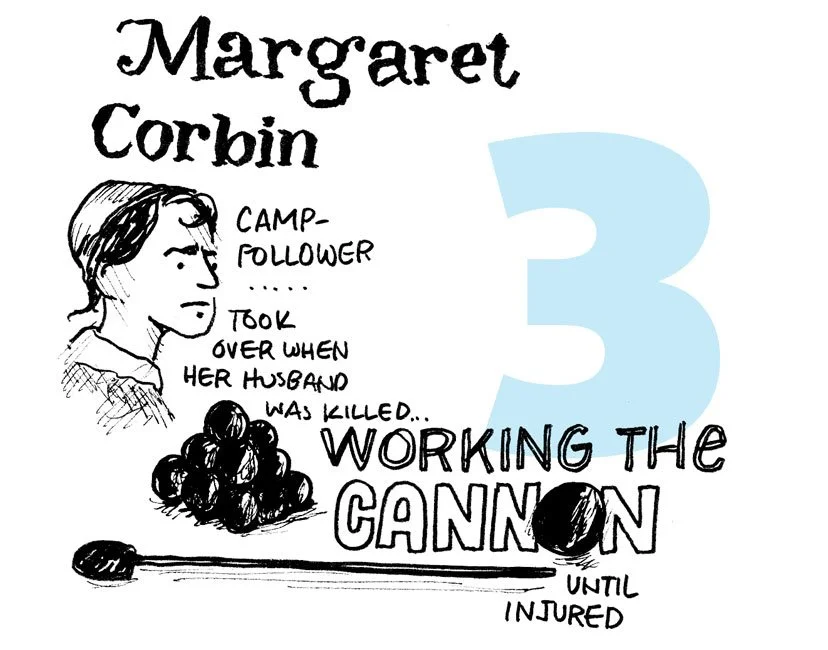

Margaret Corbin

Many assume that women avoided the front lines of the Revolutionary battles but Margaret Corbin was like many wives — a camp follower. These women traveled along with the troops, taking care of cooking and laundry as well as serving as nurses and caring for the wounded.

During the Battle of Fort Washington, John Corbin was killed defending a small cannon from a Hessian assault. Margaret jumped into action, taking his place at the cannon and fighting until she sustained injuries to her arm, chest, and jaw from enemy fire. She was captured by the British but released on parole as a wounded soldier and was plagued by her injuries for the rest of her life.

She ultimately became the first woman to receive a military pension from Congress, after receiving funds in 1779.

Martha Dandridge Custis Washington

It’s easy to imagine the wives of Revolutionary officers tending to their homes, raising their children, and praying for their husbands’ safe return. The reality is many of these women actively engaged in the work of the Revolution. Few were as dedicated as Martha Washington.

With her husband serving as general of the Continental Army, she not only oversaw family and business back at Mount Vernon but she spent almost half the war with or near him as he traveled. She joined George every winter for winter encampments, where she became a beloved figure to the rank-and-file soldiers and spent time copying Washington’s letters and papers, knitting for the soldiers and visiting hospitals.

She donated personal funds to ladies’ efforts to purchase much needed supplies and linens, as well as personally responding to letters from soldiers and their families in need. As First Lady, she made caring for veterans one of her primary areas of focus.

Doodles inspired by Dr. Lindsay Chervinsky’s The Cabinet: George Washington and the Creation of an American Institution. Flip through my sketchbook here.

Deborah Sampson

Tall, broad and strong, Deborah Sampson seemed determined to fight in the Revolution. She disguised herself as a man and attempted to join an Army unit in Massachusetts but never showed up to meet her company after being recognized in town. She enlisted again in 1782 in Massachusetts, joining the Light Infantry Company of the 4th Massachusetts Regiment. Under the name “Robert Shirtliff”, Sampson served for several weeks with an elite unit.

After a skirmish with some local Tories, she was shot in her thigh and cut across her face. She begged not to be taken to a doctor and ended up removing the musket ball from her thigh herself, using a penknife and sewing needle.

Despite many close calls, her true identity wasn’t discovered until almost two years later. She received an honorable discharge and a military pension from Massachusetts.

Esther Reed

Esther was born in England, where she met Joseph Reed of New Jersey while he was studying in London. She moved with him to Philadelphia when they married and was actively engaged in his law office work. Reed became First Lady of Pennsylvania in 1778 and in 1780, published Sentiments of an American Woman. Her treatise called on the women of America to do whatever they could to serve the cause of the Revolution and for women to play a larger role in public service.

She organized fundraising across the 13 American colonies, with women contributing over $300,000* for the Continental Army — funds were ultimately used to make badly needed shirts and clothing for the soldiers.

Tragically, Esther died just shy of her 34th birthday from dysentery outbreak in Philadelphia that same year.

*About $7 million USD today, if online inflation calculators can be trusted

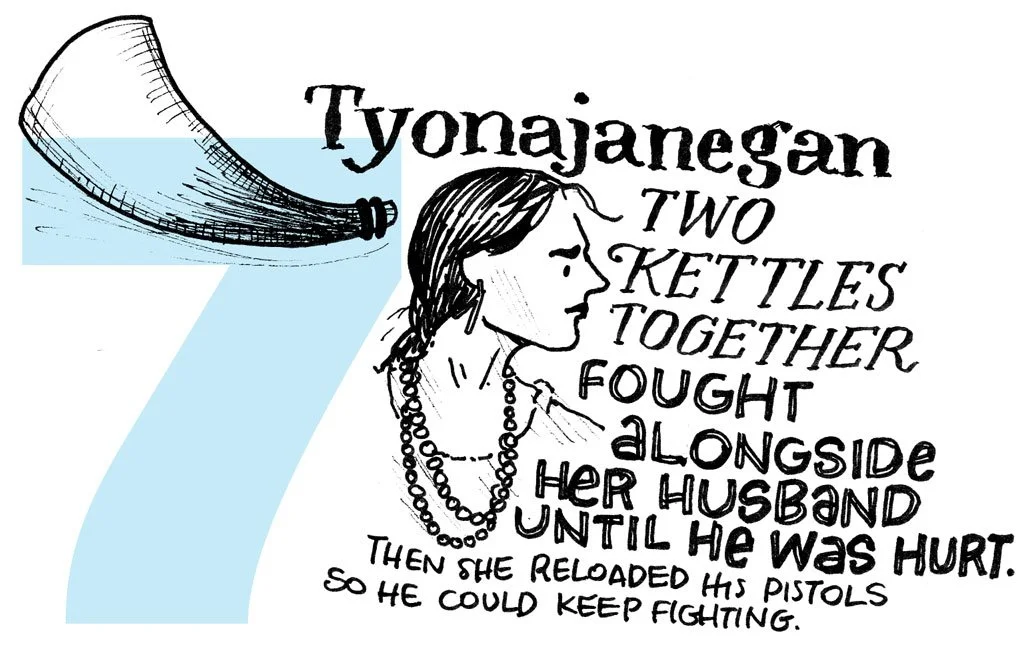

Tyonajanegan/Two Kettles Together

The Oneida Nation was a deeply important ally to the American Revolution and their support was vital to the Continental Army in New York. Tyonajanegan was responsible for warning nearby settlements that the British were surrounding Fort Schuyler, traveling throughout the countryside.

She later rode into battle with her husband, Honyere/Hon Yerry, during the Battle of Oriskany in New York in 1777 and fired her own weapons until Honyere was injured. For the rest of the battle, she loaded his pistols for him so he could continue fighting.

In appreciation of her service, General Horatio Gates instructed Colonel Gansevoort at Fort Schuyler to deliver a winter’s supply worth of rum!

Their farm was destroyed by British-supporting Iroquois because of their support for the American Revolution.

Abigail Adams

Arguably one of the strongest female voices of the Patriot cause, Abigail was an outspoken supporter of American independence, abolition, and women’s education from the beginning.

While her husband was in Philadelphia serving in the Continental Congress, Abigail kept detailed records of the political events in Massachusetts, providing much needed insight into the material losses of the war. She witnessed the Battle of Bunker Hill and shared important updates in her letters to John, including the death of their close friend Doctor Joseph Warren.

She wrote in 1775, “let us separate, they are unworthy to be our Brethren. Let us renounce them…” and a year later, she reminded her husband to “Remember the Ladies” as he served on the Declaration Committee.

Rebecca Grawl is a professional DC tour guide who has worked in public history, museum education, and tourism for more than 15 years. In addition to engaging diverse audiences in a wide variety of D.C. area tours with DC By Foot and serving as Vice President of Education for A Tour of Her Own, Rebecca can be seen on Mysteries at the Museum on the Travel Channel; is a contributor and researcher for the Tour Guide Tell All podcast; and has been featured in numerous podcasts and media outlets. Her first book, 111 Places in Women’s History in Washington, DC That You Must Not Miss, was co-authored with A Tour of Her Own founder Kaitlin Calogera. You can find Rebecca on Instagram @beccagrawl.

For more guest appearances, check out these posts:

_____________________________________________

For more people with ties to the Revolutionary War:

Of course there were